|

A few years ago I was watching a documentary on the painter Johannes Vermeer (note: I know very little about oil painting) when one of the art historians said something that made my brain implode in a good way. The art historian pointed out how Vermeer's paintings are so lifelike not just due to their perfect proportions and perfect depth of field, but because of the ways in which Vermeer mixed and used colors, such that, depending on the light source within each painting, the colors of objects situated next to one another would reflect off one another based on the color and texture of each object and the source of light illuminating them, creating a sort of interplay of light and color as it would be taken in by the human eye.

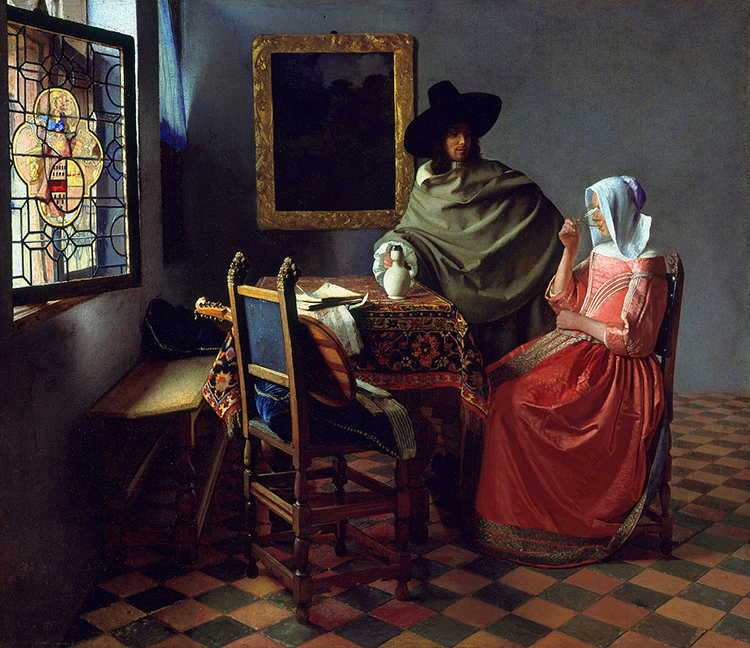

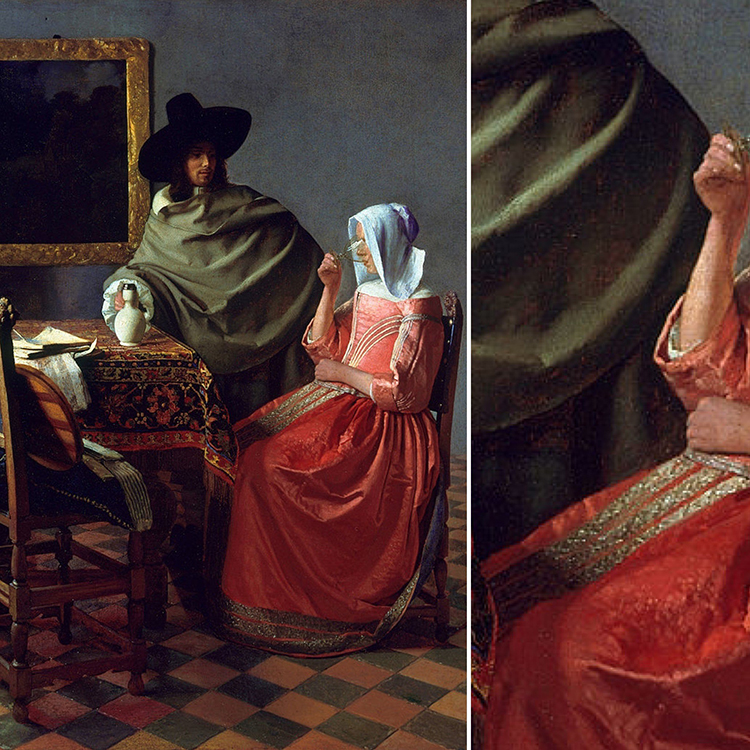

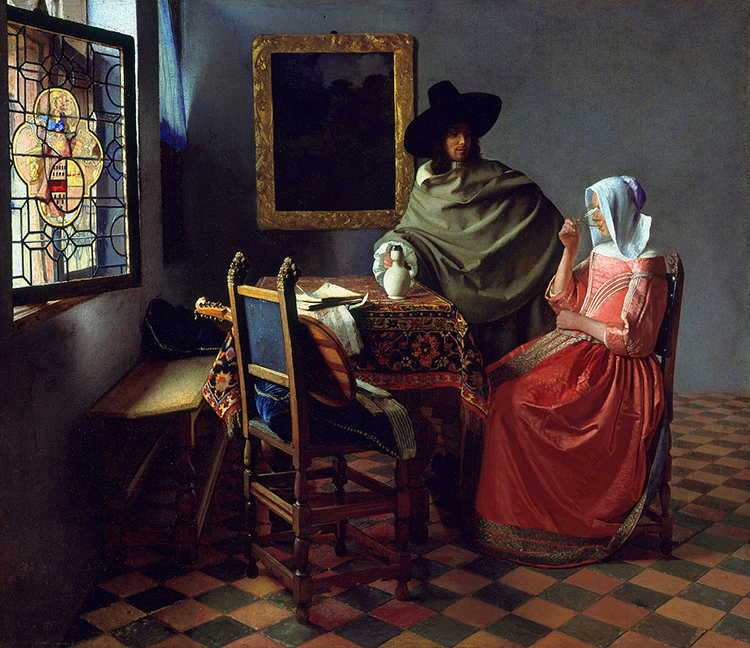

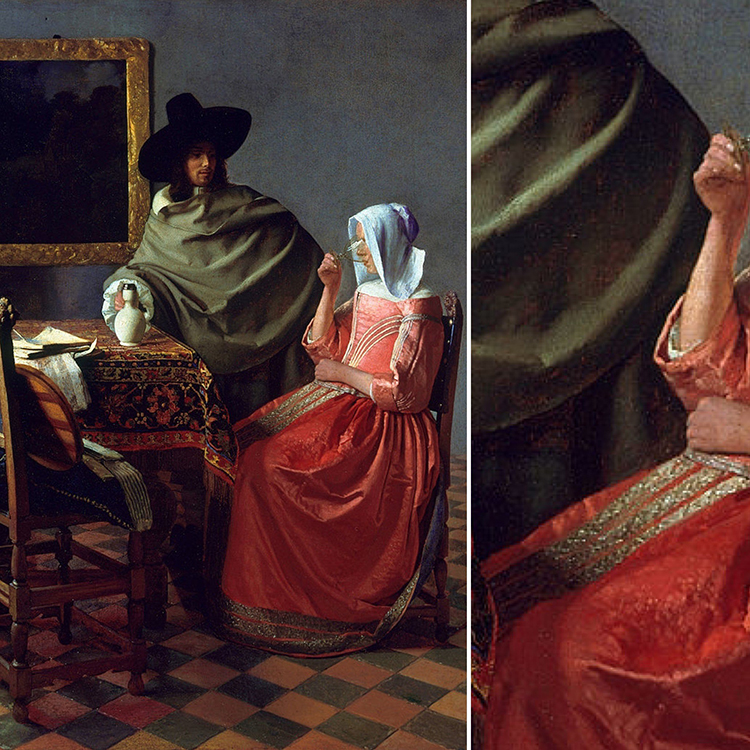

For example, in Vermeer's The Wine Glass the light source is an open window on the left. On the righthand side of the painting, a man wearing a green cloak stands next to a woman who is seated and wearing a pink dress. Some of the daylight coming in through the open window before them illuminates the woman's pink dress and refracts the color of her dress onto the shadowy portions of green fabric of the man's cloak within the creases directly facing the woman's dress.

Here's a closer look:

Another example of Vermeer's use of color in this particular painting is the sunlight passing through the blue curtain onto the wall next to it, how the blue of the curtain, and the yellow of the golden frame beside it, are reflected in the space of wall between them.

I think about Vermeer and his colors when I'm working on creating character dynamics in scenes that will offer a convincing amount of verisimilitude and dimensionality for readers. While realist paintings aim to show one scene suspended in time as it is truly perceived by the human eye, stories aim to show scenes moving through time as they are truly perceived and felt by human minds and hearts. The ways in which point of view illuminates character aspects, and how these characters' aspects refract off one another, changes from moment to moment, character to character, while the life histories and personality surfaces of characters remain consistent, as is the case with real people. Unlike Vermeer's paintings, character refractions don't show up in the form of actual images, but as actions and reactions characters have to and with one another.

The thing about people, and thus characters, is that there's so much more than meets the eye. That's what stories do that paintings don't: depict the complexities that come when conscious beings move through time and space with or against one another. While it's impossible to literally see into the intangible, subterranean depths of another person, insofar as what they think and feel, we can observe glimmers of who a person is—what lurks beneath their surface—by observing their particular actions and reactions to others who are actively in the throes of their own lives as well. These momentary refractions, when point of view sheds light on one character and that character's illuminated aspects bounce off the other character's surface in particular ways through subsequent actions and reactions, it is an equation for the type of scene in which two are better than one at creating a realistic lens through which readers perceive the intangible, subterranean aspects of who these characters are.

For example, if a protagonist, in prior scenes of a story, has reacted tersely and dismissively whenever her mother or boyfriend have complimented her, and she later reacts as though she is truly validated by a compliment from her best friend, it says something to readers, either about the nature of her relationships with her mother and boyfriend vs. her friend, or about the sort of compliments that affirm her in ways she needs or prioritizes. Her different reactions show something about her in relation to specific others. Readers recognize characters as being true-to-life when they are distinct, consistent in and of themselves, and react in ways that are relevant to who they are in tandem with the narrative.

When two characters in a scene together haven't been fleshed out enough, such that no light is shed on their particularities, their dialogue and interactions might read as canned, overly directed, or overly expositional, because nothing about who they are under the surface is being illuminated or refracted to suggest there is really someone in there under the surface. When characters are fleshed out, and a light is shed on one character's particularities, and the other character reacts in a way that is not consistent with their other reactions or what the readers already know about them, then readers will not be convinced that the interaction is "real."

Creating scenes that move through time and space convincingly comes down to point of view illuminating the right aspects and characters having fitting reactions that allow readers to witness their motivations within the context of each other and the narrative. Sounds simple enough, right? I kid—not simple, but a fun challenge.

This is why fiction, like oil painting, is an art form that can be mastered. One type of mastery is offering our readers a story they will receive as we intend it to be received, which requires a lot of practice, not just at writing scenes, but at being invested in our own lives, observing what is seemingly lurking beneath the surface of other people through the glimmers of ourselves refracting off of them, or what is seemingly lurking beneath the surface of ourselves through the glimmers of others refracting off of us.

|